[fusion_builder_container hundred_percent=”no” equal_height_columns=”no” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” background_position=”center center” background_repeat=”no-repeat” fade=”no” background_parallax=”none” parallax_speed=”0.3″ video_aspect_ratio=”16:9″ video_loop=”yes” video_mute=”yes” border_style=”solid” flex_column_spacing=”0px” type=”legacy”][fusion_builder_row][fusion_builder_column type=”1_1″ type=”1_1″ background_position=”left top” background_color=”” border_color=”” border_style=”solid” border_position=”all” spacing=”yes” background_image=”” background_repeat=”no-repeat” padding_top=”” padding_right=”” padding_bottom=”” padding_left=”” margin_top=”0px” margin_bottom=”0px” class=”” id=”” animation_type=”” animation_speed=”0.3″ animation_direction=”left” hide_on_mobile=”small-visibility,medium-visibility,large-visibility” center_content=”no” last=”true” min_height=”” hover_type=”none” link=”” first=”true”][fusion_text]

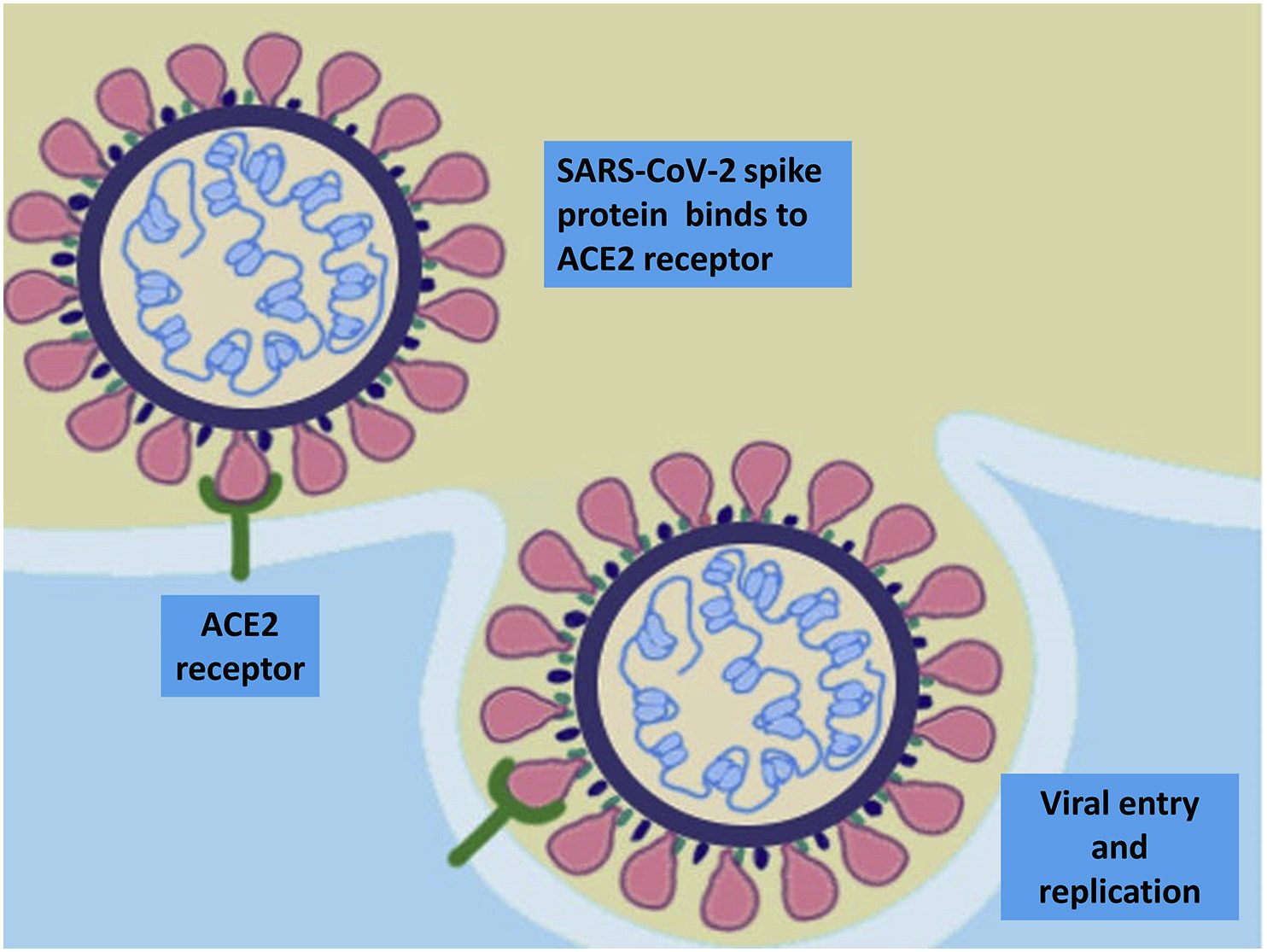

SARS-CoV-2’s S protein is the key.

COVID-19 is not a disease we want to get. Even once you’ve “recovered,” the long term effects on the microbiome won’t be known for years to come. This is all unprecedented and scary, and one could be forgiven for falling into despair, right?

-

Practice physical (not social!) distancing! Staying, at minimum, 6 feet away from other people and minimizing your time indoors when outside our homes goes a long way towards keeping you safe.

-

Wear a mask if you are near people who are not in your immediate family.

-

Eat plant-based or plant-forward: our beneficial gut microbes use fiber as their energy source to maintain our gut health and balance our immunity. Eating 30 or more different plants per week is associated with microbial diversity and improved health (9).

-

Minimize the consumption of refined sugars, emulsifiers and saturated fat. Disease promoting gut microbes feed on these foods and replicate to cause inflammation (13, 14, 15).

-

Minimizing alcohol, tobacco and environmental toxins when possible. These toxins are associated with promotion of the same microbial imbalance we are trying to prevent (16).

-

Exercise at least 30 minutes daily. Moderate exercise is associated with increased gut microbiome health (10).

-

Prioritize 7-8 hours of restful sleep every night. Our bodies need rest to thrive and lack of sleep is associated with poor microbiome diversity (11).

-

Go out into nature as much as possible. Breathing fresh air, getting vitamins from the sun and exposure to natural environments for at least 120 minutes per week is associated with optimal health (8).

-

Manage your stress by being mindful of what you are reading, watching and listening to so as not to overload yourself with negative news. Try to stay present and focus on the now. Stress has been associated with poor health outcomes, especially when one is not in any real danger (12).

-

Maintain social connectivity. In the age of COVID, this is easier said than done, though there are some tricks: make sure you are talking to your friends and loved ones over social media or a video platform, and maybe plan an physically distanced get together at a park or other outdoor venue (remember to always wear your mask!)

-

Lastly, and probably most importantly, is being patient with yourself and your body, giving yourself grace and allowing your good habits to take effect without searching for quick solutions that often don’t yield lasting healing.

-

Zuo T, Zhang F, Lui GCY, Yeoh YK, Li AYL, Zhan H, Wan Y, Chung ACK, Cheung CP, Chen N, Lai CKC, Chen Z, Tso EYK, Fung KSC, Chan V, Ling L, Joynt G, Hui DSC, Chan FKL, Chan PKS, Ng SC. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020 Sep;159(3):944-955.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.048. Epub 2020 May 20. PMID: 32442562; PMCID: PMC7237927.

-

Redd WD, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection in the United States: a multicenter cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:765.e2–767.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.04.045

-

Zhong, P., Xu, J., Yang, D. et al. COVID-19-associated gastrointestinal and liver injury: clinical features and potential mechanisms. Sig Transduct Target Ther 5, 256 (2020). https://doi.org/1

-

0.1038/s41392-020-00373-7

-

Shreiner AB, Kao JY, Young VB. The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31(1):69-75. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000139

-

Kho ZY, Lal SK. The Human Gut Microbiome – A Potential Controller of Wellness and Disease. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1835. Published 2018 Aug 14. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01835

-

Clapp M, Aurora N, H

-

errera L, Bhatia M, Wilen E, Wakefield S. Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health: The gut-brain axis. Clin Pract. 2017;7(4):987. Published 2017 Sep 15. doi:10.4081/cp.2017.987

-

De Luca F, Shoenfeld Y. The microbiome in autoimmune diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2019;195(1):74-85. doi:10.1111/cei.13158

-

White, M.P., Alcock, I., Grellier, J. et al. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health a

-

nd wellbeing. Sci Rep 9, 7730 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44097-3

-

McDonald, D., Hyde, E., Debelius, J., Morton, J., Gonzalez, A., Ackermann, G., . . . Knight, R. (2018, June 26). American Gut: An Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research. Retrieved December 29, 2020, from https://msystems.asm.org/content/3/3/e00031-18

-

Cook MD, Allen JM, Pence BD, Wallig MA, Gaskins HR, White BA, Woods JA. Exercise and gut immune function: evidence of alterations in colon immune cell homeostasis and microbiome characteristics with exercise trai

-

ning. Immunol Cell Biol. 2016 Feb;94(2):158-63. doi: 10.1038/icb.2015.108. Epub 2015 Dec 2. PMID: 26626721.

-

Smith RP, Easson C, Lyle SM, et al. Gut microbiome diversity is associated with sleep physiology in humans. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0222394. Published 2019 Oct 7. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222394

-

Karl JP, Hatch AM, Arcidiacono SM, et al. Effects of Psychological, Environmental and Physical Stressors on the Gut Microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2013. Published 2018 Sep 11. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02013

-

Bancil AS, Sandall AM, Rossi M, Chassaing B, Lindsay JO, Whelan K. Food additive emulsifiers and their impact on gut microbiome, permeability and inflammation: mechanistic insights in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2020 Dec 18:jjaa254. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa254. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33336247.

-

Zhang M, Yang XJ. Effects of a high fat diet on intestinal microbiota and gastrointestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2

-

016;22(40):8905-8909. doi:10.3748/wjg.v22.i40.8905

-

Hansen NW, Sams A. The Microbiotic Highway to Health-New Perspective on Food Structure, Gut Microbiota, and Host Inflammation. Nutrients. 2018;10(11):1590. Published 2018 Oct 30. doi:10.3390/nu10111590

-

Engen PA, Green SJ, Voigt RM, Forsyth CB, Keshavarzian A. The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: Alcohol Effects on the Composition of Intestinal Microbiota. Alcohol Res. 2015;37(2):223-236.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]